Shedding the Shoulds: Freeing Yourself Up via Person-Centred Therapy, Attachment Theory And EMDR (Part 1)

Imagine you're a child, and you draw a picture. Your parent/ carer says, "Wow, you're such a good artist!" You feel great! But next time, you show them another drawing and they say, "That's not very good..." Suddenly, you feel not-so-great.

In this collection of articles I will explore how we take on ‘shoulds’ during our formative years and how we can free ourselves up to be ourselves through the lens of 3 different theories/ therapies:

Person-Centred Approach (PCA)

Attachment Theory

Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR)

Person-Centred Approach (PCA)

Carl Rogers (the founder of the PCA) noticed that we start to believe we're only lovable or valuable when we meet certain expectations—when we’re “good,” “smart,” “polite,” or “successful.” These expectations are what he called "conditions of worth."

How do we take these on?

As children, we naturally want love, approval, and safety—especially from our parents or caregivers. But when that love feels conditional (like, “I’m only loved when I get good grades” or “when I don’t cry”), we start to internalise those conditions.

We think:

“I’m only good if I make people happy.”

“If I fail, I’m not worthy.”

“If I cry, I’m weak and unlovable.”

So instead of being our true selves, we try to be the version of ourselves that earns love and approval—even if it means hiding our feelings or denying our needs.

Why it matters in therapy

Rogers believed that these "conditions of worth" can cause anxiety, low self-esteem and inner conflict. In therapy, his person-centred approach helps people reconnect with who they really are underneath all those conditions—so they can feel accepted, valued, and whole just for being themselves, not for meeting someone else's standards.

How does this link into Attachment Theory?

Same developmental process, different languages

Emma Tickle argues that the PCA and Attachment Theory are essentially two ways to describe the same thing: how early relationships shape our sense of self-worth and our expectations of others:

Rogers (PCA): Children internalise conditions of worth—unspoken rules ("I’m only lovable if I behave or succeed") often shaped by caregivers.

Bowlby & Ainsworth (Attachment Theory): Children form internal working models—mental templates about whether they’re worthy of love and whether others will be there for them again often shaped by caregivers..

How do attachment styles and conditions of worth align?

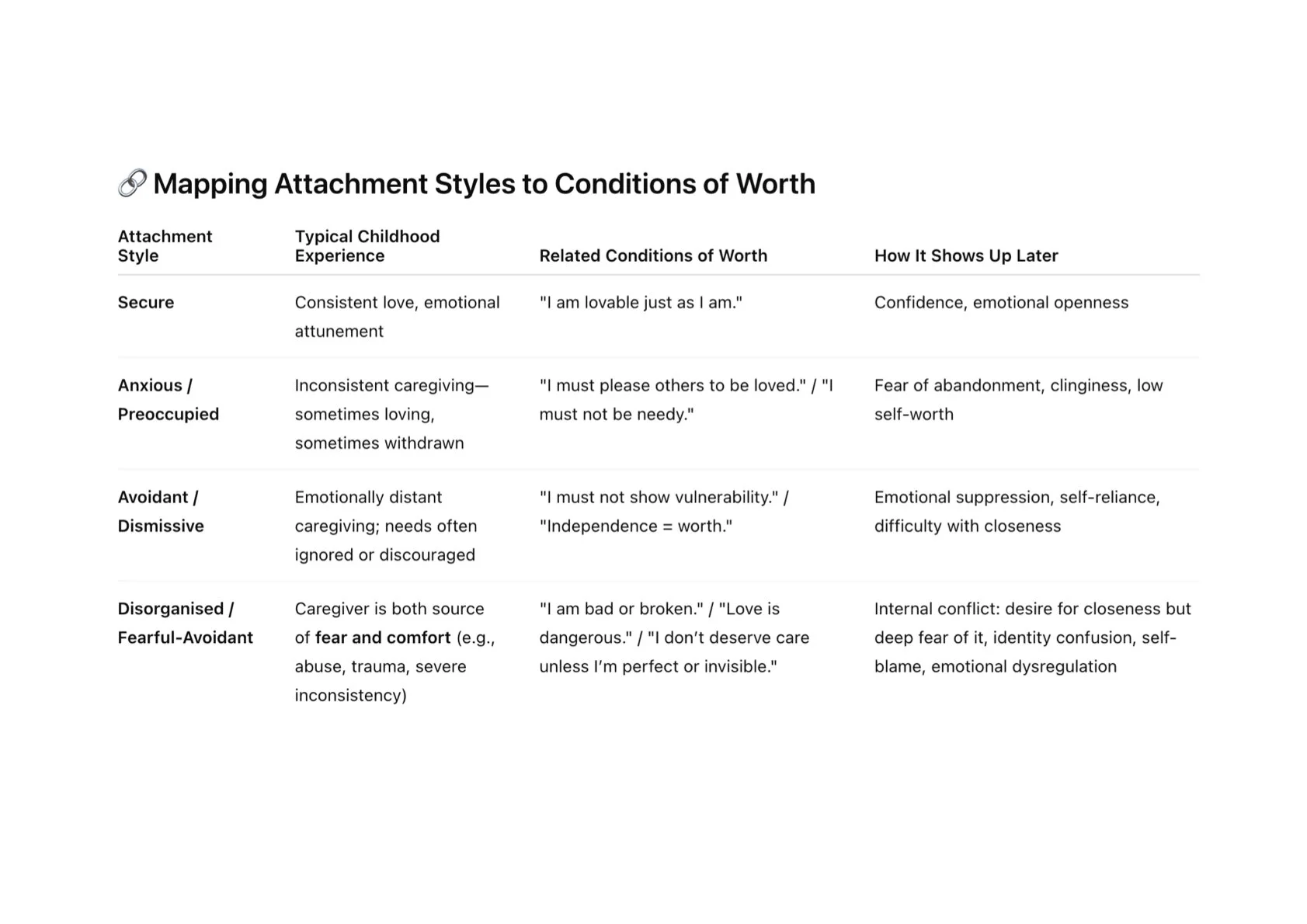

In her work, Emma Tickle shares that attachment styles and conditions of worth are essentially reflecting the same process. I have extended upon Tickle’s work to include disorganised (or fearful/avoidant) attachment. An idea of how attachment styles might map to conditions of worth, as well as how these might show up on our adult life, can be seen below:

Mapping Attachment Styles To Conditions Of Worth

Impact In Therapy

The PCA focuses on helping someone discover and release the conditions of worth they’ve internalised i.e. the ‘shoulds’ via which we might unknowingly be living our life. The attachment therory lens provides insight into *how* those conditions developed—who modelled them and what patterns arose.

In summary

Early interactions set “if...then” (or ‘shoulds’) rules in our mind e.g. “If I behave, then I’m loved.”

These become internalised conditions of worth/ self-beliefs/ attachment styles.

When we view ourselves and our patterns of relating via PCA and attachment theory we can begin to understand ourselves more. With this understanding we can begin to unravel ways that we operate that are no longer so helpful and free ourselves from unhelpful conditioning in order to reconnect with our authentic self.

As we free ourselves up to become ourselves we gain more trust in who we are and our related self-worth. When we feel better about ourselves we are likely to feel more at ease when relating to others e.g. rather than feeling fearful of forming a meaningful attachment to others we could feel more confident that we are worthy of connection and therefore less afraid of forming a meaningful attachment. In other words we are also likely to see our pattern of relating, or our attachment style, change to some degree.

Interested in exploring this further?

In Part 2 of this series of articles I will be exploring the lesser known attachment style of disorganised attachment or fearful-avoidant attachment.